By Ken Olsen

(Copyright 2018)

Charles Savukas’ South Pacific deployment almost sounds like a page from an exotic travel brochure: fishing, swimming and exploring the white sands and turquoise waters of Christmas Island, when he wasn’t working as secretary to a naval commander.

He had no health problems to report when the Navy sent its annual questionnaire in the years that followed. Remarkable, given that Savukas witnessed a series of thermonuclear bomb tests between March and July 1962, standing out in the tropical sunshine, his only protection a pair of special dark glasses. Watching endless fireballs boiling up on the horizon. Feeling the superheated blast waves pulsing over him. Hearing the sonic booms that rocked the buildings on the tiny island.

Then, a decade ago, Savukas was diagnosed with colon cancer – a first in his family history. That was followed by radical surgery that saddled him with a restricted lifestyle and a different perspective on his island time. “We wore badges to record the amount of radiation we received and were told it was safe,” says Savukas, a member of American Legion Post 628 in Lilly, Pa. “Until 2007, I thought I was great.”

In some ways, Savukas is fortunate compared to other servicemembers dispatched to the South Pacific during decades of U.S. nuclear weapons tests. The government tracked his health for 20 years after he left the Navy, eventually acknowledging his exposure to ionizing radiation and the resulting cancer, then belatedly provided Savukas some compensation. That’s far more than thousands of other atomic veterans have received.

“The government really did them wrong,” says Michael Blecker, a Vietnam War combat veteran and executive director of Swords to Plowshares, a veterans organization based in San Francisco. “They didn’t take any real precautions. They made no effort to conduct any follow-up. Then they deny everybody’s (health-care) claims when there’s no controversy they were there.”

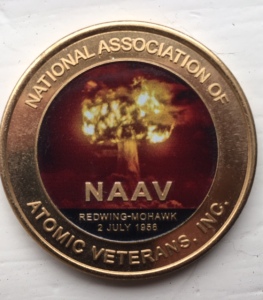

Fred Schafer, of the National Association of Atomic and Nuclear Veterans, being interviewed for a documentary about the military’s atomic weapons testing.

Many veterans never saw a dime, says Fred Schafer, national commander of the National Association of Atomic & Nuclear Veterans (NAAV) and a Legionnaire who served on a Navy oiler during some of the 1962 nuclear tests. “When they could finally talk about it, it was too late,” he adds, referring to scores of veterans who were dead by 1996, when the U.S. government finally lifted an order that had prohibited veterans from revealing their participation in atomic bomb tests. Too late to apply for VA medical care and benefits. Too late to receive the recognition they were promised.

Atomic veterans have only a few years – until July 2022 – to file claims with a Justice Department compensation program. That would leave them only with VA, which often treats them with the same doubt and denial it gives veterans dealing with the health effects of Agent Orange, Gulf War Illness, or burn-pit exposure in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“Right here in Oregon, VA has been treating us great,” Schafer says. “In other states, atomic veterans can’t get the time of day.”

‘THE GREAT THERMONUCLEAR SEA’

The U.S. military conducted approximately 200 nuclear weapons tests between 1945 and 1962, most often in the Marshall Islands. The location was ideal because it was under U.S. control, sparsely populated and had reliable weather, author Simon Winchester wrote in his book “Pacific.” Yet the atomic weapons testing was so pernicious that Winchester dubbed the Pacific “the Great Thermonuclear Sea.”

Approximately 200,000 U.S. servicemembers participated, along with British, Australian, Canadian and French troops as well as civilian scientists, engineers, technicians and support staff. More than a million people were exposed to ionizing radiation during Operation Crossroads, Operation Frigate Bird and dozens of other atomic bomb tests at home and abroad, Schafer says. That includes his aunt, who the U.S. Forest Service sent to Nevada in 1952 to witness two atomic bomb tests. She died of breast cancer at 56.

Participants were threatened with treason if they talked. “We were told we had cleared top security,” Schafer says. “That felt real good to a 19-year-old.” Even today, he encounters atomic veterans who don’t realize they are allowed to talk about their experience or exposure to lethal ionizing radiation.

DENIAL

Atomic veteran Orville Kelly and his wife, Wanda, founded the National Association of Atomic Veterans in the late 1970s (“Nuclear Veterans” was added to the name later) and lobbied Congress to help the soldiers, sailors and airmen who were suffering as a result of their radioactive service. Lawmakers insisted the nuclear weapons tests had never taken place, Schafer says.

Atomic veteran Orville Kelly and his wife, Wanda, founded the National Association of Atomic Veterans in the late 1970s (“Nuclear Veterans” was added to the name later) and lobbied Congress to help the soldiers, sailors and airmen who were suffering as a result of their radioactive service. Lawmakers insisted the nuclear weapons tests had never taken place, Schafer says.

Meanwhile, a young attorney named Gordon Erspamer filed suit on behalf of the National Association of Radiation Survivors (NARS) and other veterans groups, including Swords to Plowshares. Erspamer had a personal interest in their cause. He had been fighting VA on behalf of his late father, Ernest, who contracted leukemia as a result of his participation in atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in 1946, and his mother’s right to survivor’s benefits.

The NARS case reached the Supreme Court in 1985. Erspamer was not only fighting on behalf of radiation survivors, but he was also challenging a Civil War-era law that prevented all veterans from paying an attorney more than $10 to represent them no matter how complicated the case, Blecker says. He also took issue with the fact that veterans could not appeal VA decisions in court.

Up to then, “(VA’s) Board of Veterans’ Appeals was the highest level of appeal,” Blecker says. “If you couldn’t appeal an administrative decision outside of the agency, then VA had the ultimate authority.”

In the course of the NARS litigation, Erspamer deposed Ron Abrams, who was part of the quality review team in VA’s Central Office. Abrams verified that VA was not meeting its legal obligation to assist veterans filing claims for service-related injury and illness. “My testimony indicated that the quality of regional office adjudication sucked, to put it in layman’s terms,” Abrams says. “VA was violating the due process rights of veterans.”

The agency harassed Abrams until he left the agency five years later, he says. He then joined the National Veterans Legal Services Program (NVLSP) and went on to help the nonprofit win major precedent-setting cases on behalf of veterans, as its co-executive director.

Although Erspamer eventually lost the NARS case at the Supreme Court, the lawsuit changed the way Congress – and to a certain extent VA – dealt with atomic veterans. Congress repealed the $10 limit on what veterans could pay attorneys and created the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims in 1988. Erspamer filed the new court’s first case – challenging VA’s decision to deny his mother survivor’s benefits in the wake of his father’s death from an illness related to his military service.

Meanwhile, The American Legion played a part in getting the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims created, Abrams says. It was accomplished without undermining the service office system so integral to helping veterans. And it’s an important part of Erspamer’s legacy; he died of a brain tumor in 2014.

VA eventually opened the door to disability and medical care claims from some atomic veterans. Today, former servicemembers with one of two dozen types of cancer who served in the testing areas between 1945 and 1962 are presumed to have been exposed to deadly ionizing radiation and qualify for VA benefits. But many atomic veterans still don’t qualify for VA assistance. That includes more than 4,000 Enewetak Atoll cleanup veterans, dispatched to mitigate the radioactive contamination of a highly toxic portion of the Marshall Islands in the late 1970s.

Keith Kiefer, NAAV national vice commander, wants to change that. He’s working to persuade Congress to provide VA benefits to Enewetak cleanup veterans and extend the deadline for all atomic veterans to apply for help from the Justice Department program that expires in 2022.

Kiefer knows the issue firsthand. He came home temporarily sterile from his service as an Air Force communications specialist on Enewetak and has since developed several autoimmune diseases, thyroid problems and a blood-clotting disorder. Once private physicians connected his illnesses to his exposure during the Enewetak cleanup, they recommended he apply for medical care from VA.

That proved fruitless.

“VA says none of the veterans involved in the cleanup were exposed to enough radiation to qualify,” says Kiefer, who has been so busy helping other atomic veterans file claims that he hasn’t taken time to revisit his own case. “It’s not right. But I’ll do what I can to change it.”

BENEFITS AND RECOGNITION

In the early 1990s, Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) after years of lawsuits, including those brought by the workers who mined and processed uranium during the Cold War. RECA has provided lump-sum payments to about 30,000 uranium workers and civilians who lived downwind from U.S. nuclear weapons test sites, as well as approximately 4,000 veterans.

Savukas received a check for $75,000 after providing proof of service on Christmas Island during the atomic testing and verification of his medical condition, money he would happily trade for never having had cancer. Meanwhile, his VA claim has been denied twice. Even if he prevails, the $75,000 likely would be deducted from any VA benefits.

Savukas’ experience is typical. Veterans have generally had better success getting a straight answer and timely adjudication from the Justice Department program, Kiefer says. Most veterans, however, probably don’t know they even qualify. Savukas got a tip from his son, who came across the program while working for a government subcontractor.

Schafer has yet to apply for any of the programs, even though his exposure stories are harrowing. For example, his ship was ordered to sail though the blast area soon after an atomic bomb was detonated to test an experimental ship-washing system. Schafer and his shipmates were told they were part of an atomic bomb test.

“We were told it wasn’t harmful,” he says, “and that it was a safe test.”

In retrospect, that didn’t make sense. A person could see the bones in his hands or the ribs of the man in front of him after the bombs went off, Schafer says: “It was like a giant X-ray.”

He has not developed cancer or any other radiation-related illnesses.

Schafer returned home to Oregon after his Navy service and started a successful career as a salesman. He was at an American Legion post in Lebanon, Ore., in the 1980s when a discussion with a stranger there led him to join NAAV. He’s been national commander of the group for four years and Oregon state commander for the past two decades.

Not only has the state NAAV chapter fought on behalf of Oregon veterans, it has taken up the cause of refugees from the Marshall Islands who moved to the state because their homeland is contaminated from the atomic bomb tests. The atomic veterans also have helped the islanders secure Oregon driver’s licenses and health insurance.

As the veterans poisoned by the nuclear arms race dwindle – membership in NAAV has dropped from a peak of 100,000 to about 1,500 today – the organization is opening its doors to U.S. servicemembers who were exposed to depleted uranium from armor-piercing tank ammunition and bunker-buster bombs, and is working to help the widows of atomic veterans apply for VA survivor’s benefits.

As much as anything, the group wants the federal government to formally acknowledge their service by approving the long-delayed Atomic Veterans Service Medal. “I’m proud of my service,” Schafer says. “This is a form of recognition they promised. It says, ‘Yes, we did this to our guys.’”

This story originally appeared the June 2018 issue of The American Legion Magazine.